A load of bunk, a myth – or does the yeti really exist? Almost any Sherpa will tell you that it does, that it is lurking out there in the cold and therefore that it is very real. Then why has one not been seen? Well, it has, though apart from the Sherpas themselves and their cousins, the Tibetans, not frequently.

In November 1903, a Himalayan explorer by the name of William Hugh Knight sighted one near Gangtok in Sikkim. A few years before, a British India Army surgeon, Major Laurence Augustine Waddell, sighted a set of large footprints at 17,000 feet in north-east Sikkim though not the animal that made them. “These were alleged to be the trail of the hairy wild men who are believed to live amongst the eternal snows,” wrote Waddell in his 1900 work Among the Himalayas.

Since then a number of Europeans have come across the animal in various parts of the Himalayas, at various times and at varying altitudes. In 1925, N.A. Tombazi, a geologist employed by the Bombay merchant firm of Ralli Brothers, observed a yeti at 15,000 feet on Zemu Glacier in Sikkim. André Roch, a member of the 1952 Swiss Everest Expedition, caught a fleeting glimpse of one in the forests below Namche Bazaar. In 1970, British climber Don Whillans saw one scamper along a ridge in the Annapurna Sanctuary, and in 1986 Italian climber Reinhold Messner saw two in the same day while walking through the forests north-east of Everest.

More than simply lodged in the collective imagination of a tribal people, the yeti does have a documented existence extending across the full 1,500-mile width of the Himalayan arc, from the Pamir in Afghanistan to the mountainous jungles of eastern Asia. But a few prerequisites are necessary for a yeti’s presence in such a hostile environment, primarily an adequate food supply. So lets clear away that misconception. Whatever it really is, the yeti is not an abominable snowman, being most at home in the sparse high-altitude forests and yak pastures. It sups at the table of the snow leopard. It seems that this large feline, once thought to be near extinction, is a messy feeder. The yeti is not.

The yeti and snow leopard have always lived together, not exactly side by side, all cosy like, but in close proximity. The yeti, according to Himalayan lore, lives at least partly off scraps of food left over by the snow leopard.

Doubters claim that not enough food exists at high altitude to sustain a large carnivore. Wrong. Yaks are large. Their summer pastures top out at 5,500 metres (18,000 ft). However they are grazers. The yeti will eat whatever is available: herbs, lichen, snowcock, martins, voles or a larger order of mammals if it can catch them. In the stunted forests above 4,000 m. (13,120 ft) and up to the high pastures at 5,500 m. musk deer, tahr and serow are present and they are good meat-bearing creatures whose flesh is much appreciated by hungry predators.

But one thing is certain – deforestation at high altitude and the proliferation of trekkers and climbers threaten the yeti habitat. Although this is the case in Nepal and northern India, the wilds of Outer Mongolia and Siberia, being vast and sparsely populated, provide excellent breeding space for large primates accustomed to living in subarctic conditions. I know how vast and rugged these regions are because I have flown over a good slice of them in a light aircraft (see the First Perestroika Flight).

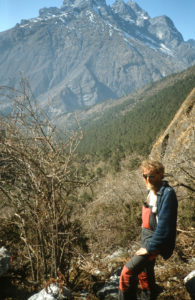

Convinced of the yeti’s existence, in the mid-1980s I decided to investigate. Though they are not exactly docile, one can safely write about them without fear of being pursued for libel. Yetis do not litigate. They are curious by nature, timid perhaps, and largely nocturnal in their wanderings. After two reconnaissance trips, I selected the area south of Cho Oyu, situated on the frontier between Nepal and Tibet, as the most promising yeti-hunting grounds. Wild and back then relatively inaccessible, the Ngozumba Valley had a snow leopard population, a record of sightings by Sherpas, the existence of yeti artefacts in two nearby monasteries and footprints in snow reported by the Everest expeditions of the early 1950s, the Daily Mail find-the-yeti expedition of 1954. I am not a mystic, nor an expert on Buddhist mythology. The accompanying photo gallery bares witness to what I saw.