Journalist, writer, traveller and occasional explorer, but above all witness to six decades of change. Sixty years in which mankind’s ability to wreak havoc or bring peace and prosperity have never been so great, a time during which regimes crumbled, civilisations subsided as others surged, and values changed. Progress has transformed virtually every avenue of human endeavour from medicine, architecture and transportation to communications. Never has our ability to make war been more absolute, or our capacity to eradicate famine and disease more tangible. When I began as a foreign correspondent, mechanical typewriters and transmitting copy by “news telephones” to unseen speed-typists were the standard. Now ever more powerful computers and electronic mail do the job in a fraction of the time. No more wire photos, even mobile telephones take pictures. Curiosity and good sense were the principal prerequisites of a proud profession; now it seems that every aspiring reporter must have a degree in journalism. We were always moving targets, but less so 60 years ago. “Fake” news only became a concern when The Donald made it one. Back whenever it was probably called propaganda and few mistook it for anything else. Fixed deadlines have faded into oblivion, yet news twitters ever onwards, and so does life.

Witness

Civil War in Switzerland? Never – at least not since 1847. The masters of direct democracy have another way of settling differences. They hold a referendum. Following the Second World War a separatist movement took root in the French-speaking Jura region of Canton Berne. It unleashed a bitterly fought campaign, with some arson attacks by a youth wing called Les Béliers. The Free Jura campaigners did not want nationhood or fusion with neighbouring France, but their own French-speaking canton within the Swiss Confederation with the medieval city of Delémont as capital. After years of strife a countrywide referendum was held in September 1978 and the split was democratically confirmed. The antics of the Béliers and the demagogic rantings of Roland Béguelin, leader of the Free Jura movement, caused a few snickers in London, then confronted with a serious IRA problem, and provided a good excuse for this correspondent to travel through an enchanting countryside, getting to know the people, their concerns and aspirations for The Sunday Telegraph.

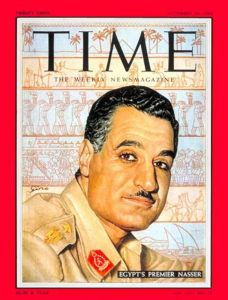

That was my first “war” assignment. The next was more serious. The build-up to the Six Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbours began in mid-May 1967 when Gamal Abdel Nasser dismissed the UN peace observers and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli  shipping. Three weeks later Israel launched a preemptive air and land offensive that destroyed Egypt’s military aviation and trapped its army in the Sinai. In the run-up to hostilities Nasser ordered the expulsion of all British journalists in Cairo. Fleet Street had no representatives in the Egyptian capital, leaving the British press uncovered in the Middle East’s most powerful nation. A Canadian, I was not affected by the ban and volunteered to fill the gap. The Daily Telegraph accepted, and this intrepid veteran of the Jura liberation campaign was launched on a hot warzone assignment. The only problem was access. The Israelis had bombed Cairo’s International Airport, shutting it down to all traffic. Not knowing a thing about North African geography, I figured I could enter Egypt from neighbouring Libya by hiring a taxi in Benghazi to take me 800 miles across the Western Desert.

shipping. Three weeks later Israel launched a preemptive air and land offensive that destroyed Egypt’s military aviation and trapped its army in the Sinai. In the run-up to hostilities Nasser ordered the expulsion of all British journalists in Cairo. Fleet Street had no representatives in the Egyptian capital, leaving the British press uncovered in the Middle East’s most powerful nation. A Canadian, I was not affected by the ban and volunteered to fill the gap. The Daily Telegraph accepted, and this intrepid veteran of the Jura liberation campaign was launched on a hot warzone assignment. The only problem was access. The Israelis had bombed Cairo’s International Airport, shutting it down to all traffic. Not knowing a thing about North African geography, I figured I could enter Egypt from neighbouring Libya by hiring a taxi in Benghazi to take me 800 miles across the Western Desert.

Benghazi was in chaos. The British Army maintained a presence at the old Italian Duke of Aosta barracks on the outskirts of the city, and British officers commanded the Cyrenaica Camel Corps. The Libyans perceived Britain as an ally of Israel. The citizens of Benghazi wanted all British influence removed. When British troops entered the city to rescue Jewish merchants from the mob, rioters attacked their armoured column, setting several Saladin armoured cars afire, trapping their crews inside.

An acrid smell hung over the city. I hired a taxi to fetch me at my hotel the following morning for the overland journey to Cairo. No show. The airport was shut as the Algerian Air Force had decided to fly to Egypt’s assistance of but quickly found their MiGs had nowhere to land east of Benghazi. As Benghazi Airport was the closest they could get to the war zone, they sat there for the next several days before returning home.

With nothing better to do, I wandered about discretely photographing the sights, until arrested by the Benghazi police and taken to a dingy police station for interrogation. My film was confiscated and I was informed that I was being expelled from the country. The only trouble was that Benghazi had been sealed into its own seething world and there was no way I could leave. I was snatched from custody by the Cyrenaica Corps officers and taken to their barracks. They were a friendly lot but realised their future employment was in doubt as King Idris, a British puppet, was on his way out and a young Libyan colonel no one had ever heard of was stealthily taking over.

The Six-Day War was over when finally I got to Cairo, arriving from Rome on the first commercial flight. The Nile Hilton on the Corniche became my headquarters. The Raïs – Nasser – resigned a few days later but changed his mind next morning after millions of Egyptians called for him to remain. All was quiet for a time. The Egyptian authorities bussed foreign correspondents to a mystery destination so we could hear Ahmad Shukeiri, leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, describe how he was going to liberate his homeland. But Shukeiri was little more than a bag of hot air and Arab hopes soon focused on Yasser Arafat, a young engineer who headed Al Fatah. After attending several pro-Nasser rallies, all was quiet on Israel’s western flank and I returned home to Switzerland.

A year later the Telegraph asked me to return to Cairo. Soon after my arrival the War of Attrition began. The night it started with an exchange of artillery fire along the blocked Suez Canal I was almost lynched by the Cairo mob. Luckily I managed to escape. My three-month stay in Cairo ended with a case of hepatitis and I returned home to Switzerland. Lying in bed with fever, I missed the Prague Spring. Then along came an Australian nutcase who in August 1969 set fire to Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa Mosque, imagining it might hasten the second coming of Jesus Christ.

His act sent the Islamic world into frenzy, prompting King Hassan II of Morocco to convene the first Islamic Summit at Rabat a few weeks later. Attended by 25 heads of state, it changed the face of political Islam. The Telegraph requested I cover the event. Its only achievement was to ask Israel to return the Arab lands occupied during the Six-Day War. Nothing doing, said Golda Meir, unless all parties to the conflict agreed to sit down around a table and negotiate a durable peace settlement.

After the Rabat summit my life changed very little. Richard Nixon came to the White House in January 1969. In August 1971 he unhinged the dollar from the gold standard, introducing the era of floating currencies. In Switzerland the dollar began its long decline from 4.32 to the franc to parity, while sterling slipped from SF 10 to SF 2. With a mortgage to pay I began moonlighting for Bernie Cornfeld’s Investors Overseas Services, incorporated under the initials I.O.S. Ltd., at that time the world’s largest financial services company. Headquartered in Geneva, IOS was going from strength to strength, attracting big names to serve on its various boards like former West German vice chancellor Erich Mende, Kentucky’s lieutenant governor Wilson Wyatt and President Roosevelt’s son Jimmy Roosevelt.

Cornfeld was a warm and soft-spoken salesman from the Bronx with a biting choleric temper. Despite his millions Bernie “Big Bucks” was a socialist, a showman with a stutter and a penchant for nonconformity. As IOS’s services were dollar-based, and as the value of the dollar ebbed so did confidence in IOS. Its feared demise attracted a host of financial sharks, foremost being Robert Lee Vesco, a New Jersey entrepreneur with a mini conglomerate listed on the American Stock Exchange. With promises of big-buck payoffs he fomented a boardroom revolt that removed Cornfeld from control of the company he founded and instantly set about stripping the IOS group of its $2.5 billion in assets. I had left IOS by then but retained an insider’s knowledge and insider friends who kept me informed about what was going on. I wrote a series of financial features in the Sunday Telegraph that prompted a publishing offer from Praeger, the New York publisher.

What made Vesco big-name news was his contacts with the Nixon White House. He was particularly close to Nixon’s younger brother, F. Donald Nixon, and hired as his gopher Donald’s son, the none-too-bright Donald A. Nixon, known as Don-Don. He also latched on to Nixon’s Secretary of Commerce Maurice Stans and Attorney-General John Mitchell, ultimately contributing to their downfall by making a $250,000 illegal donation to the Committee to Re-elect the President. Vesco flew around the world in a corporate Boeing 707 and he owned a luxury hideaway in Costa Rica, ultimately becoming a fugitive from US justice, accused of securities fraud, embezzling more than $200 million from IOS, drug smuggling and political bribery. He settled in Cuba, where he developed high-level contacts with the Castro regime but was convicted of “economic crimes against state” in the 1980s and sentenced to prison. He was released from prison in 2005, terminally ill with lung cancer, and died in 2007.

Books

Author of eight books ranging from white collar crime exposés to adventure travel and historical novels. While compiling material for this section I discovered to my astonishment that one of my books was selling in the electronic marketplace for £222, representing I suppose a bookmark of sorts, though I don’t know why that should be and hasten to point out that not a penny of that amount goes to the author.

How an international swindler with close ties to the Nixon White House bamboozled the board of Bernie Cornfeld’s IOS empire, seized control and looted it of $220 million. He then tried to buy immunity from prosecution by making an illegal cash contribution to the Committee to Re-Elect the President, before fleeing into exile.

Published by Praeger Publishers Inc., 1974.

How the world’s biggest commercial bank used shady book-keeping practices to manipulate the foreign exchange markets and manufacture millions of dollars in profits. Mounting an aggressive legal offensive to whitewash its off-booking practices the bank and its senior employees escaped prosecution.

Published by William Morrow & Company, New York, January 1986.

Travelling the world’s most dangerous overland trade routes from the UK to Saudi Arabia in a 40-ton semi-articulated truck, braving along the way bent Turkish traffic police, Saddam Hussein’s vicious secret police and suspicious Saudi customs inspectors searching for drugs and pornography.

UK edition published by William Heinemann, 19 November 1987

A winter’s search in the shadows of Mt Everest for the elusive yeti. Hutchison is accompanied in this quest by a Sherpa family from Pangpoche and shares their customs and lifestyle while getting to know the monks of Tengboche Monastery. He follows a dual set of mysterious tracks from the high yak pastures under Cho Oyu to the forests around the village of Phortse, 20 miles southwards, but fails to sight a single yeti.

Published by Macdonald, London, 1989

A look behind the curtain of secrecy that shrouds the extreme right-wing of the Catholic Church, exposing a vast financial network and connections to organised crime. With a cast of crooks and cardinals it unveils a world of intrigue and dirty tricks that leads to the murder of Italy’s leading banker, Roberto Calvi, found hanging under London’s Blackfriars Bridge.

Published by Doubleday, a division of Transworld Publishers, September 1997

Published by the Lotus Collection, an imprint of Roli Books, New Delhi, in 2010. Paperback edition published in 2015

Frederick “Pahari” Wilson – the Raja of Harsil –was a deserter from the British Army at the time of the First Anglo-Afghan War. He introduced commercial timbering to the Himalayas, becoming the richest man in northern India and the inspiration for Rudyard Kipling’s The Man Who Would be King.

Visit the Raja of Harsil website

Published by Palimpsest Books, New Delhi, 2012

The fictionalised biography of Proby Cautley, a British engineer in India in the 19th century. A clergyman’s son from Constable country, he had one goal in life: eradicate famine from northern India. He devoted his life to building the Ganges Canal, largest irrigation project of its day, for which he was knighted by Queen Victoria.

Published as an eBook in 2013.

A fictional account of a refugee uprising in Lausanne that left the city in smouldering ruins.

Amazon lists it among its Kindle Books, retailing at $8.87

Albums

About Robert

After three years reading economics and political science at McGill University, a mediocre student at best, I forsook my studies to travel, thinking that seeing the world was more useful. I made my first trip to Europe in 1958 as a crewmember aboard a 3,200-ton Italian freighter, landing at Naples. My destination was Geneva where I planned to settle with my future wife, Bridget Pyke, who was arriving at Southampton on the RMS Queen Mary some weeks later. After three months of blissful freedom, touring parts of the UK and western Europe in a second-hand Morris Minor 1000 Convertible, fearing we were about to elope Biddy’s parents called her home. I was 20 and she was 19. A marriage was arranged the following spring, a few days after my 21st birthday, and we returned to Geneva, I to continue studying, having been admitted to the faculty of commerce at the University of Geneva. Commercial studies were not my cup of tea but the university authorities were unimpressed by my prior academic record and refused admittance to the general arts faculty. Not pleased, my days attending lectures were few and to keep off street corners and out of bars I decided to become a cub reporter, working for Switzerland’s only English-language newspaper, the Weekly Tribune.

Being slender and good looking, Biddy got a job as a clothes model. That was in 1959. Daphne, our first child, was born in July 1962. Tamara, our second, arrived in January 1964, and Chloe came six years later, in August 1970. Three more wonderful children I am unable to imagine.

Shortly after Tamara’s birth we bought an abandoned farmhouse at Le Muids in the Vaudois Jura. The property was called Les Saugeons. We moved in while transformation work was still in progress. Looking back, those were supremely happy years. Never had enough money. My wife’s passion for horses insured we remained poor, but we lived in our own house bounded by an orchard and couple of acres of pasture. With the simplest means available we built an open-stall stables in a corner of the front yard under a linden tree, and on a clear day we could look across Lake Leman onto Mt Blanc. Everything was idyllic.

The Sunday Telegraph of London had just begun publication with an editorial staff entirely separate from the Daily Telegraph. My godmother was a friend of the deputy foreign editor and she spoke to him about her footloose godson in Geneva. The Sunday Telegraph had no correspondent in Switzerland. To my surprise I was offered the job.

Working from the pressroom of the UN’s European Headquarters was rather boring. Correspondents like myself were fed boxed news. We had the UN Disarmament Conference to cover. Extremely boring. And the Geneva Round of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). Even more boring. Then I was introduced to Bernie Cornfeld and began moonlighting for Investors Overseas Services (IOS), at the time the world’s largest financial services combine. My life changed dramatically with the 1967 Six-Day War. Colonel Nasser expelled all British correspondents. But I was Canadian. The Telegraph thought sending me to Cairo was worth a try, so off I went, to the alarm and concern of my wife.

From 1961 to 1976, I remained a correspondent of the Sunday and Daily Telegraph. In 1967 and 1968 I covered the aftermath of the Six-Day War from Cairo. Returning to Geneva, a bout of hepatitis kept me bedridden during the Prague “Springtime” but I was sufficiently recovered to report on the 1969 Islamic Summit at Rabat, which reshaped the face of political Islam. Coming down with “Abukir Bay” hepatitis had an unexpected upside. It saved me from becoming a serious dipsomaniac as I was left with no taste whatsoever for alcohol and a moderate liking for wine.

The floating of the dollar in August 1971 heralded the downfall of IOS and, though not connected, the collapse of our marriage. I had already said goodbye to IOS but the prospect of being permanently separated from my wife and children meant emotionally hard times. I kept looking across the lake at Mt Blanc and dreamed of one day setting foot upon its summit.

A 1966 assignment for the Sunday Telegraph sent me to Chamonix to report on the feared disappearance of American climber Gary Hemming and his British mate Mick Burke while attempting to rescue two German climbers stranded on Les Drus. They were caught in a freak snowstorm. Climbers from all over Europe gathered in Chamonix to await the outcome of one of the most dramatic rescue attempts in Alpine history. I was directed to the Bar National, owned by Maurice Simon, which served as headquarters for les grimpeurs anglais. Grim looking members of the climbing fraternity occupied every chair and table in the place. The atmosphere was crackling with tension. The recue team included two Chamonix guides and two climbing friends of the stranded Germans. René Desmaison, under contract to Paris Match, joined them on the second day. They reached the Germans two days later. Hemming and Burke decided to evacuate the Germans by abseiling down the American Direct Route opened by Hemming four years before. The weather finally broke and then 10 million people followed the rescue operation covered by French television and two helicopters. Everyone got down safely, the Germans after 10 days roped to a ledge; one of a second group of rescuers died, tangled in his rope.

As climbing became more popular more accidents occurred and more Brits lost their lives in the Alps. In those days the capital of Anglo-Saxon climbing was Leysin, due almost entirely to the efforts of two men, American John Harlin and Scotsman Dougal Haston. I never met either but occasionally I was called upon to report on their exploits. Their headquarters was the world-famous Club Vagabond, founded by another Canadian Alan Rankin. Club Vagabond was also home to the International School of Mountaineering, founded by John Harlin in 1965. Harlin fell to his death in March 1966 while attempting to open a direct route up the North Face of the Eiger and Haston, who had summited Everest, was killed in January 1977 by an avalanche while skiing above Leysin. Largely because of Harlin’s charisma, Leysin became base camp for leading Anglo-Saxon climbers like Layton Kor, Don Whillans, Doug Scott, Peter Boardman and Royal Robbins. It was a fabled place and I dreamed of becoming part of the scene.

Under Swiss law our matrimonial regime was dissolved by court order, but not the marriage itself as Biddy never returned the final papers; divorce became by default legal separation. She would have been happy to resume married life as if nothing had happened but there was no backtracking. Our eldest “chickens” had flown the roost, Daphne to Israel, where she eventually married, and Tammy to Montreal, obtaining a degree in sociology from the University of Montreal and a graduate diploma in international development from Ottawa. The court had given custody of Chloe to her mother.

I rented a studio apartment at Les Praz de Chamonix but moved my Swiss residency papers to Leysin. By the time I arrived in the hill resort, the Club Vag – once the hottest show in town – was on a long downward slide. Many people have asked why Leysin? Well, there was its climbing tradition. By then the author of two books and having helped my semi ex-wife to look after horses for a decade, I wanted to climb. I love horses. They are like big dogs. But they are very dependent and require a great deal of care and attention. I found a feeling of solidarity existed in the climbing community, whether amateur or professional, that I wanted to tap into. However climbing is a tricky business and well into my middle life I was too old to learn all the tricks, so out of concern for my safety I climbed with professional guides. Two marked my short climbing career – Jean-Claude Charlet and Pinson Devouassoud, both of Argentières in the upper Chamonix valley and members of the Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix.

With Jean-Claude I traversed Mt Blanc, finally setting foot on its summit, and climbed the Aiguille Verte, a far more technical proposition. With Pinson I twice skied the Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt and climbed numerous lesser peaks in France and Switzerland.

Those were excellent times. Biddy returned with Chloe to Hudson Heights, the village near Montreal where she was brought up and where we were married. Soon after the spirits of my youth began telling me to go to the Himalayas and search for the yeti, an animal that few believed existed. Since seeing Eric Shipton’s photos of its footprints in the early 1950s I was convinced that it did. During a 1985 reconnaissance, I met Gyalzen Sherpa. We trekked together and I stayed a few days at his home in Pangpoche. He and his family reaffirmed my conviction. I returned in 1987 and spent a winter with them, travelling through the valleys and across the glaciers of Khumbu. In my case not seeing was believing, especially after hearing on several occasions animal footfalls around my tent and seeing its spoor in the snow a few days later.

I returned to Leysin and wrote a book about my Himalayan experiences. At Chalet Sybil, which I shared with two friends, I found that someone had been sleeping in my bed. That someone was Lucia Kaeppeli, a druggist who on weekdays lived and worked in the lakeside town of Rolle, between Nyon and Lausanne. We became friends and eventually started living together. Thirty years later we are still together.

Jean-Claude Charlet asked me to be the photographer on a December 1990 expedition of French cancer patients to Mount Kilimanjaro. We summited Africa’s highest mountain (5,890 metres) by the Western Breach route a few days before Christmas. Although on the equator, it snowed the night before. The solidarity and determination of the 10 members of that expedition helped make it one of the richest experiences of my life. When I reached Charles de Gaulle on our return I telephoned Lucia to tell her we were safely back; my emotions were so wound up that I cried on the phone. “Why are you crying?” she asked. I couldn’t explain.

My articles in The Financial Post of Toronto on international fraud, and high-level corruption surrounding the sale of Canadian nuclear reactors to Argentina won a National Business Writing Award, followed during the 1970s by three citations for outstanding investigative reporting. Looking back all these years later there were many outstanding people who marked my career. Among the journalists I knew and whose skills and integrity inspired me were Charles Raw, Godfrey Hodgson and Murray Sayle of the original Sunday Times Insight Team, Paul Lewis of the New York Times, Michael Brown of the Daily Express, Tariq Ali Foda of Cairo’s Rose al-Yusuf, martyred because of his progressive religious views, and Financial Post editor Neville Nankivel. I had the honour of knowing and working with two outstanding literary agents: Peter Shepherd of Harold Ober Associates, New York, and Gillon Aitken, of what was then Aitken & Stone, London. During my Indian travels I was encouraged in my research by Mussoorie-based writer, photographer and philosopher Ganesh Saili, and by Delhi antiquarian, art lover and publisher Ashok Agrawal, a man of incredible sensitivity and insight.

My thanks to Dan Urlich, long-time Leysin friend and software engineer, who encouraged me to create this website and showed me how to do it, and to my daughter Tamara, an IT specialist who also guided me, cleaning up the technical tangles I frequently got into. And of course Lucia for her patience and advice.