Civil War in Switzerland? Never – at least not since 1847. The masters of direct democracy have another way of settling differences. They hold a referendum. Following the Second World War a separatist movement took root in the French-speaking Jura region of Canton Berne. It unleashed a bitterly fought campaign, with some arson attacks by a youth wing called Les Béliers. The Free Jura campaigners did not want nationhood or fusion with neighbouring France, but their own French-speaking canton within the Swiss Confederation with the medieval city of Delémont as capital. After years of strife a countrywide referendum was held in September 1978 and the split was democratically confirmed. The antics of the Béliers and the demagogic rantings of Roland Béguelin, leader of the Free Jura movement, caused a few snickers in London, then confronted with a serious IRA problem, and provided a good excuse for this correspondent to travel through an enchanting countryside, getting to know the people, their concerns and aspirations for The Sunday Telegraph.

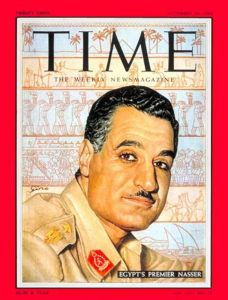

That was my first “war” assignment. The next was more serious. The build-up to the Six Day War between Israel and its Arab neighbours began in mid-May 1967 when Gamal Abdel Nasser dismissed the UN peace observers and closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli  shipping. Three weeks later Israel launched a preemptive air and land offensive that destroyed Egypt’s military aviation and trapped its army in the Sinai. In the run-up to hostilities Nasser ordered the expulsion of all British journalists in Cairo. Fleet Street had no representatives in the Egyptian capital, leaving the British press uncovered in the Middle East’s most powerful nation. A Canadian, I was not affected by the ban and volunteered to fill the gap. The Daily Telegraph accepted, and this intrepid veteran of the Jura liberation campaign was launched on a hot warzone assignment. The only problem was access. The Israelis had bombed Cairo’s International Airport, shutting it down to all traffic. Not knowing a thing about North African geography, I figured I could enter Egypt from neighbouring Libya by hiring a taxi in Benghazi to take me 800 miles across the Western Desert.

shipping. Three weeks later Israel launched a preemptive air and land offensive that destroyed Egypt’s military aviation and trapped its army in the Sinai. In the run-up to hostilities Nasser ordered the expulsion of all British journalists in Cairo. Fleet Street had no representatives in the Egyptian capital, leaving the British press uncovered in the Middle East’s most powerful nation. A Canadian, I was not affected by the ban and volunteered to fill the gap. The Daily Telegraph accepted, and this intrepid veteran of the Jura liberation campaign was launched on a hot warzone assignment. The only problem was access. The Israelis had bombed Cairo’s International Airport, shutting it down to all traffic. Not knowing a thing about North African geography, I figured I could enter Egypt from neighbouring Libya by hiring a taxi in Benghazi to take me 800 miles across the Western Desert.

Benghazi was in chaos. The British Army maintained a presence at the old Italian Duke of Aosta barracks on the outskirts of the city, and British officers commanded the Cyrenaica Camel Corps. The Libyans perceived Britain as an ally of Israel. The citizens of Benghazi wanted all British influence removed. When British troops entered the city to rescue Jewish merchants from the mob, rioters attacked their armoured column, setting several Saladin armoured cars afire, trapping their crews inside.

An acrid smell hung over the city. I hired a taxi to fetch me at my hotel the following morning for the overland journey to Cairo. No show. The airport was shut as the Algerian Air Force had decided to fly to Egypt’s assistance of but quickly found their MiGs had nowhere to land east of Benghazi. As Benghazi Airport was the closest they could get to the war zone, they sat there for the next several days before returning home.

With nothing better to do, I wandered about discretely photographing the sights, until arrested by the Benghazi police and taken to a dingy police station for interrogation. My film was confiscated and I was informed that I was being expelled from the country. The only trouble was that Benghazi had been sealed into its own seething world and there was no way I could leave. I was snatched from custody by the Cyrenaica Corps officers and taken to their barracks. They were a friendly lot but realised their future employment was in doubt as King Idris, a British puppet, was on his way out and a young Libyan colonel no one had ever heard of was stealthily taking over.

The Six-Day War was over when finally I got to Cairo, arriving from Rome on the first commercial flight. The Nile Hilton on the Corniche became my headquarters. The Raïs – Nasser – resigned a few days later but changed his mind next morning after millions of Egyptians called for him to remain. All was quiet for a time. The Egyptian authorities bussed foreign correspondents to a mystery destination so we could hear Ahmad Shukeiri, leader of the Palestinian Liberation Organisation, describe how he was going to liberate his homeland. But Shukeiri was little more than a bag of hot air and Arab hopes soon focused on Yasser Arafat, a young engineer who headed Al Fatah. After attending several pro-Nasser rallies, all was quiet on Israel’s western flank and I returned home to Switzerland.

A year later the Telegraph asked me to return to Cairo. Soon after my arrival the War of Attrition began. The night it started with an exchange of artillery fire along the blocked Suez Canal I was almost lynched by the Cairo mob. Luckily I managed to escape. My three-month stay in Cairo ended with a case of hepatitis and I returned home to Switzerland. Lying in bed with fever, I missed the Prague Spring. Then along came an Australian nutcase who in August 1969 set fire to Jerusalem’s Al Aqsa Mosque, imagining it might hasten the second coming of Jesus Christ.

His act sent the Islamic world into frenzy, prompting King Hassan II of Morocco to convene the first Islamic Summit at Rabat a few weeks later. Attended by 25 heads of state, it changed the face of political Islam. The Telegraph requested I cover the event. Its only achievement was to ask Israel to return the Arab lands occupied during the Six-Day War. Nothing doing, said Golda Meir, unless all parties to the conflict agreed to sit down around a table and negotiate a durable peace settlement.

After the Rabat summit my life changed very little. Richard Nixon came to the White House in January 1969. In August 1971 he unhinged the dollar from the gold standard, introducing the era of floating currencies. In Switzerland the dollar began its long decline from 4.32 to the franc to parity, while sterling slipped from SF 10 to SF 2. With a mortgage to pay I began moonlighting for Bernie Cornfeld’s Investors Overseas Services, incorporated under the initials I.O.S. Ltd., at that time the world’s largest financial services company. Headquartered in Geneva, IOS was going from strength to strength, attracting big names to serve on its various boards like former West German vice chancellor Erich Mende, Kentucky’s lieutenant governor Wilson Wyatt and President Roosevelt’s son Jimmy Roosevelt.

Cornfeld was a warm and soft-spoken salesman from the Bronx with a biting choleric temper. Despite his millions Bernie “Big Bucks” was a socialist, a showman with a stutter and a penchant for nonconformity. As IOS’s services were dollar-based, and as the value of the dollar ebbed so did confidence in IOS. Its feared demise attracted a host of financial sharks, foremost being Robert Lee Vesco, a New Jersey entrepreneur with a mini conglomerate listed on the American Stock Exchange. With promises of big-buck payoffs he fomented a boardroom revolt that removed Cornfeld from control of the company he founded and instantly set about stripping the IOS group of its $2.5 billion in assets. I had left IOS by then but retained an insider’s knowledge and insider friends who kept me informed about what was going on. I wrote a series of financial features in the Sunday Telegraph that prompted a publishing offer from Praeger, the New York publisher.

What made Vesco big-name news was his contacts with the Nixon White House. He was particularly close to Nixon’s younger brother, F. Donald Nixon, and hired as his gopher Donald’s son, the none-too-bright Donald A. Nixon, known as Don-Don. He also latched on to Nixon’s Secretary of Commerce Maurice Stans and Attorney-General John Mitchell, ultimately contributing to their downfall by making a $250,000 illegal donation to the Committee to Re-elect the President. Vesco flew around the world in a corporate Boeing 707 and he owned a luxury hideaway in Costa Rica, ultimately becoming a fugitive from US justice, accused of securities fraud, embezzling more than $200 million from IOS, drug smuggling and political bribery. He settled in Cuba, where he developed high-level contacts with the Castro regime but was convicted of “economic crimes against state” in the 1980s and sentenced to prison. He was released from prison in 2005, terminally ill with lung cancer, and died in 2007.