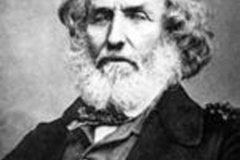

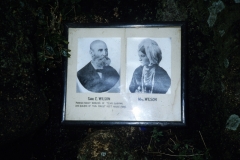

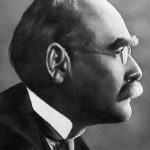

“He led a life that would have been the envy of kings,” was the opinion of Rudyard Kipling, who visited the hill station of Mussoorie in the summer of 1888, five year’s after Frederick Wilson’s death. Kipling, a young journalist at the time, vacationed with his friends Professor and Mrs S.A. Hill at the Charleville Hotel, whose construction Wilson had financed. Pahari Wilson was already a legend in the hills of northern India. A deserter from the British Army, he had gone to ground 40 years before in the remote Bhagirathi valley, where he survived by hunting musk deer. Soon after leaving the Charleville, Kipling wrote The Man Who Would Be King, his most famous short story. Wilson was the model for the fictional Daniel Dravot, the story’s central character.

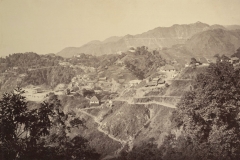

I first heard of Frederick Wilson from ecologist Sunderlal Bahuguna during a 10-day journey we made together through in the backcountry of Tehri Garhwal in the spring of 1987. I was fascinated. After boarding a bus at Uttarkashi, our first stop was Bhatwari. Here in 1864 Wilson had built one of his das mila bungalows that he used when travelling downriver. Later in the day as we moved upriver, Bahuguna pointed out Wilson’s forest mansion at Harsil, decidedly a sprawling affair.

A staunch conservationist, son of a forester, Bahuguna was hardly an unbiased source. As co-founder of the Chipko Movement, his mission was to protect the Himalayan forests from unscrupulous loggers. He explained that Wilson had introduced commercial timbering to the Himalayas. “He was the devil who began it all,” Bahuguna said. Selling sleepers (crossties) to British engineers engaged in expanding India’s rail network had made Wilson vastly wealthy. But Bahuguna, I discovered, held a grudging admiration for the innovative villain from Yorkshire.

From everything Bahuguna told me, Wilson might well have become the king of Upper Tangnore, the name then given to that part of the Bhagirathi basin where Harsil is located, had Lord Someshwar, a local deity, not decided otherwise. Bahuguna’s tales of Wilson haunted me for close to a decade. I was convinced an exposé of the timberer’s baroque lifestyle would make fascinating reading. And so I began researching what became The Raja of Harsil, collecting in the process a large archive of images that documented Wilson’s existence. Much of the material assumed historical significance as – almost systematically it seemed – Wilson’s legacy was erased from the countryside. One by one his houses and workshops were destroyed by the march of time, much as the forests he clear-cut had fallen victim to the same progression most of us refer to as “progress”. Frederick Wilson’s Garhwal is a photographic essay about an incredible adventurer, and of the curse that Lord Someshwar laid upon him.

For anyone interested in obtaining the Wilson album, it can be ordered by pressing here [sorry, the link is not yet working].